Libor's Reaching Point of Pain for Companies With Big Debt Loads

This article by Sally Bakewell for Bloomberg may be of interest to subscribers. Here is a section:

Companies that took out floating-rate loans knew they would have to pay more to borrow once rates started rising, but they haven’t experienced real increases for years. Even when the Federal Reserve started hiking rates in December, many companies did not have to pay higher rates on their loans until Libor breached key levels, because of the way their floating rates are calculated. Rising interest payments would only add to pain for U.S. borrowers that are already suffering from falling profits and higher default rates. And Libor could rise further-- JPMorgan Chase & Co. strategists recently forecast it could reach 0.95 percentage point by the end of this month.

There will be some companies “for which it might become an issue," said Neha Khoda, a high-yield credit strategist at Bank of America Corp. With Libor having risen above key levels like 0.75 percentage point, many issuers have to think about how they will pay the extra interest, she said. Three-month Libor now stands at 0.86 percentage point, and has been rising as new money market fund rules curb investor demand for companies’ short-term debt.

Interest rates on loans in the leveraged loan market are calculated by starting with a benchmark borrowing rate like three-month Libor and adding a margin known as a "spread." About $230 billion of the loans in the market have a minimum benchmark level, or "floor," equal to 0.75 percentage point, meaning that even if Libor has fallen below that level, the borrower must pay the minimum plus the spread. Most of the debt in the $900 billion leveraged loan market has Libor floors, which is often set around 1 percent.

High yield issuers of floating rate notes are at an obvious disadvantage as the prospect of short-term rates rising is priced in. That represents an important consideration because floaters are one of the primary destinations for bond investors seeking to hedge their exposure to rising interest rates since they would avail of higher yields.

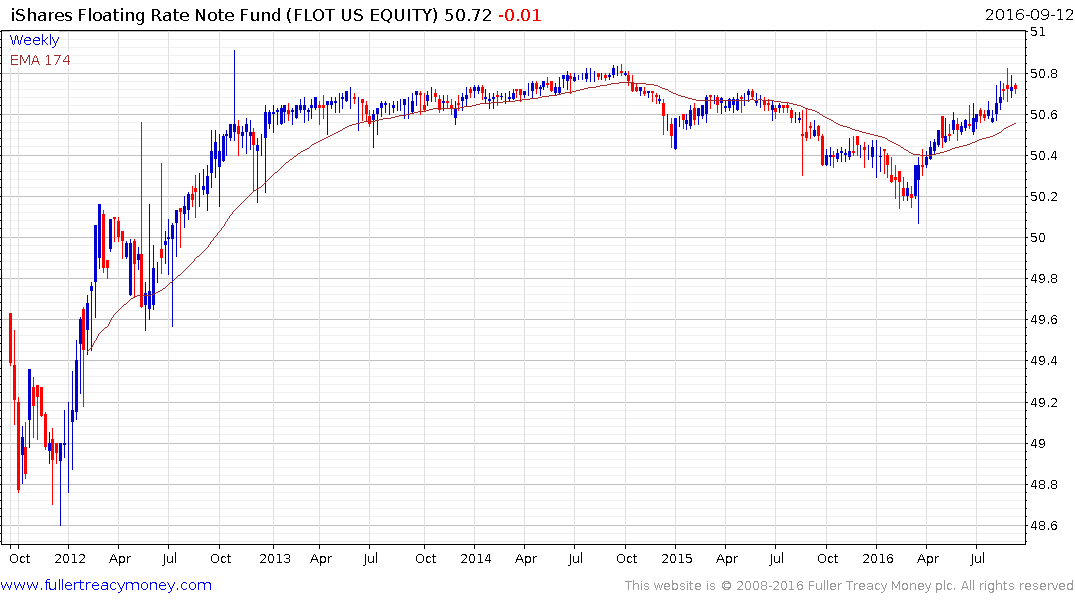

The iShares Floating Rate Bond ETF has almost $3 billion under management and rallied to break a more than yearlong downtrend in March. It continues to rally, and since investors have limited choice in what hedges they purchase, a sustained move below the trend mean would now be required to question potential for additional upside.

Meanwhile the higher rates move, the greater pressure issuers will be put under to sustain higher coupons. The temptation to call in the bonds where possible and/or refinance for fixed rates subject to the provisions of respective prospectuses will grow commensurately. Where this is not possible higher debt repayments could detract from spending on growth and R&D which would be bad news for related stocks.

3-month LIBOR remains on a recovery trajectory.