Rising Chinese Inflation to Show Up in U.S. Imports

BEIJING - When garment buyers from New York show up next month at China's annual trade shows to bargain over next autumn's fashions, many will face sticker shock.

"They're going to go home with 35 percent less product than for the same dollars as last year," particularly for fur coats and cotton sportswear, said Bennett Model, chief executive of Cassin, a Manhattan-based line of designer clothing. "The consumer will definitely see the price rise."

Inflation has arrived in China. And after Tuesday's release of crucial financial statistics by China's central bank, few economists expect Beijing officials to be able to tame rising prices any time soon.

While American importers of Chinese goods will feel the squeeze, the effect on American consumers may be more subtle and the overall impact on United States inflation may be minimal.

There are simply too many other markups along the way - from transportation to salesclerks' wages - that affect the American retail prices of Chinese-made products. Excluding those markups, imports from China are equal to little more than 2 percent of the overall American economy.

The bigger consumer impact is in China itself. As China's booming economy enables more of its own citizens to buy the goods pouring out of its factories, Chinese consumers are feeling inflation directly. And Beijing is increasingly worried about the social unrest that could result.

In China, consumer prices were 5.1 percent higher in November than a year earlier, according to official government data. And many economists say the official figures actually understate the rate of inflation, which might in reality be twice as high.

"Four percent, China can bear it - beyond 5 percent, people will complain a lot," said Huo Jianguo, president of the Chinese

Academy of International Trade and Economic Cooperation here.

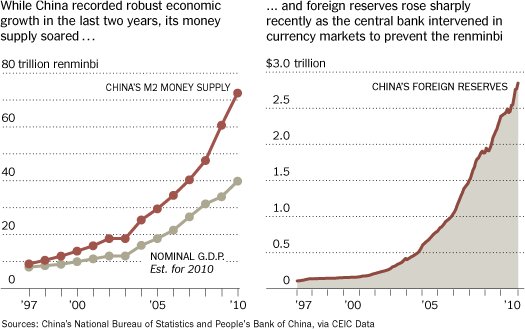

Higher global commodity prices, as well as rising wages in China, play roles in the increasing cost of Chinese goods. But economists say the main reason for the inflation now is China's foreign exchange reserves, which surged by a record amount in the fourth quarter.

The central bank has been pumping out currency at an ever-accelerating pace over the past decade to limit the renminbi's appreciation against the dollar. That strategy has helped preserve a competitive advantage of Chinese exporters by keeping their prices relatively low on global markets - while also protecting the jobs of tens of millions of Chinese workers in export factories.

David Fuller's view A number of central banks were printing

money in excess of GDP growth before the 2008 meltdown - to keep their currencies

competitive - and we know that quantitative easing followed that traumatic event.

This led to record levels of paper money sloshing around the system, which the

CBs hoped would reduce the risk of deflation by jumpstarting GDP growth once

again.

This

policy was largely successful - arguably too successful for Asian-led stronger

economies which experienced no worse than growth recessions and are now fighting

inflation, mainly from surging commodity prices which were no suprise for subscribers.

(See also last Thursday's Comment of the Day.)

When

commodity price inflation becomes an official concern, as it clearly has in

many countries, it is also a headwind for equities to the extent that it poses

a threat to GDP growth and corporate profitability. This headwind intensifies

as interest rates increase.

Subscribers

can expect some turbulence in stock markets while inflation remains near the

front pages of newspaper business sections. However, commodity price inflation

is a bigger threat to bond markets, especially where investors drove yields

to record lows due to deflationary concerns.

Equities,

rather than bonds, are a hedge against inflation provided interest rates do

not rise sufficiently to risk recession. That risk does not appear high because

there is little evidence of wage inflation, or scope for it, in the West. However

there are pockets of wage inflation in the stronger economies.

I think

that this disparity in inflationary pressures between the stronger and slower

growth economies is largely responsible for changes in relative strength among

stock markets over the last two to three months. For instance, the S&P 500

became a relative strength leader while inflationary concerns have weighed on

India, as you can see from this weekly

5-year overlay chart.

This

change in relative performance may persist for a while longer, until inflationary

pressures have been fully discounted, but I do not think that it is a long-term

factor. When relative performance next swings back in favour of India over Wall

Street, that is likely to be an important signal.